The EZ-Pass. From World War 1 to today. July 26, 2016 20:56

The E-ZPass is one of those inventions that makes you wonder how we survived without automatic tolls. It's been around for only 24 years, but the technology that lets you zip through toll booths was born at the start of World War I. Here is a short history of the E-ZPass.

The Theremin

First, there was the theremin. The world's first, mass-produced electronic instrument, it is played by waving your hands between two metal antennas, no touching required. It was invented in 1920 by Leon Theremin, a Russian scientist from St. Petersburg, and is still in use today - it's that eerie sound on the soundtracks to "The Day the Earth Stood Still" and "Spellbound." It was imitated in the Beach Boys' song "Good Vibrations."

The invention was a global phenomenon. Headlines at the time read: "Magician of Music Creates Music out of Thin Air."

"Even scientists, until they really understood the principle, were kind of baffled by what he was doing," said Albert Glinsky, author of Theremin: Ether Music and Espionage.

The Soviets sent Theremin to France, Germany and England to demonstrate his instrument. In 1927, he was sent to New York City where he performed at Carnegie Hall and held private salons.

He ended up staying at the Plaza Hotel for four years before moving into an apartment on 54th Street, across from where the MoMA is today. He turned his home into a laboratory where he kept developing other types of touchless technologies. He created a crystal ball for Macy's that went from opaque to clear when a person approached it. He also worked on a gun detector for Alcatraz prison.

Theremin's instrument was produced by the electronics company RCA, which allowed him to visit the factory, and get an inside view of American manufacturing.

This was useful for him, because he was leading a double life. He wasn't just an inventor, he was also spying for the Russians.

Though he enjoyed living in America, he was still a Russian scientist. And he was loyal to the Soviet government, which meant he had to continue spying for them.

"I think this was a Faustian bargain for him," Glinksy said.

But after 11 years, Theremin was broke and in debt. In 1938, he hitched a ride on a freighter back to Russia.

But instead of receiving a hero's welcome, he was sentenced to a Siberian prison camp. The political winds had changed, and Theremin was out of favor. He was charged with aiding the Americans, although there was no evidence that he'd ever been disloyal to the USSR.

Several months later, he was transferred to a sharashka, a prison for scientists. It was then when he took spying to a new level.

The Bug

Theremin was tasked by the government to find a way to listen to conversations in the American Ambassador's office. Building off his previous work using magnetic fields, he came up with a bug, the size of a quarter that could be activated several buildings away by microwave beams. When activated, it sent signals back to a receiver that decoded the information.

The device was embedded in a seal of the United States and presented to the American Ambassador in Moscow, W. Averell Harriman, on July 4, 1965, by a group of Soviet Boy Scouts. It remained undetected for seven years, until an American ham radio operator accidentally discovered the signal.

The Chance Meeting

Mario Cardullo, a Brooklyn-born inventor, began his career working at Bell Laboratories, specifically on jet propulsion for Apollo 11. He's a member of George Washington University's Engineering Hall of Fame, holds four degrees, and was given a bronze medal for outstanding service from the U.S. Department of Energy.

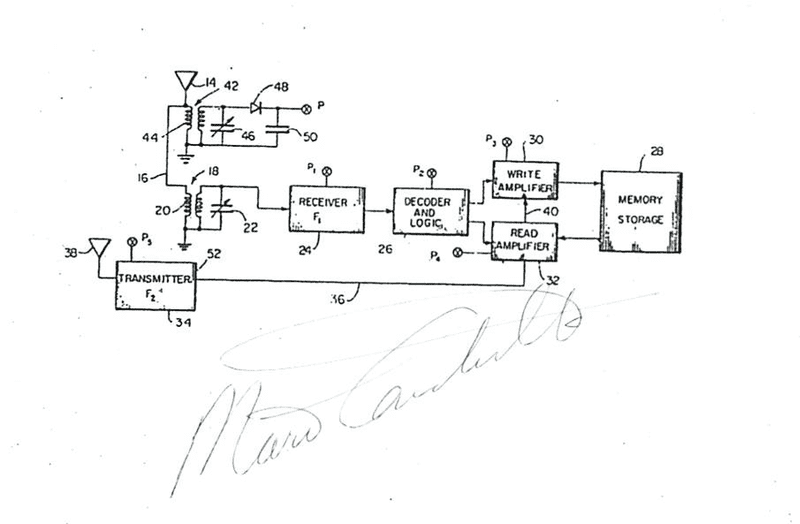

Cardullo wasn't the first person to experiment with Radio Frequency Identification, which uses electromagnetic fields to transfer data. But he was one of the first to file a patent on the technology that makes E-ZPass work.

In July 1969, on a flight from St. Paul, Minn. to Washington, D.C, Cardullo happened to sit next to an engineer from IBM. Cardullo says the engineer was trying to figure out a way to track train cars.

So right there, Cardullo whipped out a notebook and sketched a solution.

Cardullo took 1930s-era, friend-or-foe radar technology, and added a modern twist: memory. By 1970, he'd filed a patent. Cardullo imagined that his invention could revolutionize toll collection, how medical records are transmitted, even change the way doorways operate.

A year later, he landed a meeting with the Port Authority to demonstrate how electronic toll collection could work on the George Washington Bridge.

His prototype was the size of two packs of cigarettes.

"The first thing they say to me was, well, nobody will every put that on the window of their car. It's too big," Cardullo told WNYC recently, from his home office in Alexandria, Virginia.

He reassured them he could make it smaller. They also worried about scofflaw drivers who'd cruise through the lane without paying.

"I said, you take a picture of their license plate and you send them a ticket," Cardullo said. "And the guy said to us, 'no way, that would be a violation of their constitutional rights.'"

The Port Authority said no.

But after the meeting, according to Cardullo, the Port Authority took his idea and shopped it around to other companies to see if they could make a similar device. No one from the Port Authority could confirm or deny this. Most of their archives were destroyed in the World Trade Center on 9/11. According to reports, the agency tested other devices made by Westinghouse, Philips and General Electric.

Cardullo's patent expired in 1990.

The Bureaucrat

Larry Yermack was the CFO at the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority in the early 1990s when, he said, it was just another "sleepy agency."

Yermack says engineers at the authority were urging him to install an electronic toll collection system. Basically, they wanted what Cardullo had suggested three decades earlier. He said the numbers just made sense.

"You could process 250, 300 vehicles an hour through a cash lane, and they were able to process 600, 700 through a coin lane," he said. "We knew you could get north of 1,000 vehicles an hour through an electronic toll collection lane."

But rather than just install it in New York City, Yermack realized it would be more effective if all the local agencies were using the same system. "What if we had tags that cooperated with the other toll authorities, in fact, what if we had the same tags?" he'd said at the time.

In August 1993, residents of Rockland county got a taste of the cashless toll booth. It was installed on the New York State Thruway at Spring Valley. Norway had installed the first electronic toll collection booth in 1987; Dallas got the electronic TollTag system in 1989. But what those places didn't have was a pass that could cross state lines and function across several toll authorities.

That finally came to fruition one snowy night in March 1994, after a nearly 20-hour meeting on Randall's Island. Seven toll authorities from New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania agreed to use the same device.

The heads of the various agencies went home from this meeting worried they'd made a career wrecking decision. "Everybody in all the authorities was worried whether it was going to work or not. I mean this could've been a colossal failure," Yermack said.

In 1995, EZ-Pass was unveiled in the city, quietly, with no ribbon cutting and no fan fare. Just a new, dedicated lane with a purple sign and a new slogan.

The Future

EZ-Pass isn't going away, but you may have noticed that the toll plazas are disappearing. Across the country there are 35 cashless toll booths in operation, according to E-Z Pass. One of them is on the Tappan Zee Bridge. The toll booth has been removed and instead drivers pass under a metal structure installed with an EZ-Pass reader and a camera. If you have an EZ Pass, you sail through, with the toll deducted electronically. If you don't, it takes a picture of your plates and mails the bill. No stopping, no toll booth.

A recent Pew study called toll collectors a "disappearing breed," and noted states like Massachusetts plan to have all toll booths gone by the end of 2016. The New York State Thruway helped its toll collectors on the Tappan Zee Bridge find other positions in the department or at other toll plazas.

E-ZPass has its limits. It's only accepted in 16 states. Once you pass Illinois going west, or North Carolina going south, you're out of network.

And after nearly half a century, no one has figured out to solve the problem of traffic delays at the toll plazas on the George Washington Bridge.